How Jordy Went

by Jamieson Ridenhour

That was sort of Jordy in a nutshell. Of all of us, he was closest to still being a little kid. Part of that had to do with the way he looked. I had never seen real freckles before I met Jordy in the third grade, but my lack of exposure was remedied by his excesses. There was hardly an inch of exposed flesh on Jordy that wasn’t densely packed with little red marks. The biggest were almost the size of nickels and the smallest were mere pinpricks; most were round but some were irregularly shaped like ink splatters. His eyes were brown in the midst of all that red, deep and sad when he wasn’t cutting fool, which wasn’t often. His red hair was curly in a loose, out-of-control way that always made him look disheveled. In the summers he burned like a dry leaf, lobstering up almost while you watched.

Jordy confessed to me later, after the crying-in-music-class incident, that he’d been embarrassed because he didn’t know what “virgin” meant.

Of course we didn’t plan what happened. Who would plan something like that? Jordy may have said he had a plan, but he couldn’t have known, could he? There was no way to ask him later, but he couldn’t have. What I thought we had planned, that last strange weekend, was to have a sleepover at Kenny’s house and play Dungeons and Dragons. We would ride the bus home with Kenny and spend Friday night and most of Saturday at his house.

All three of us lived in a large subdivision called Riverwood. Kenny and Jordy usually preferred to hang out at my house, because my mom and step-dad were kinder than their parents. Maybe that’s not fair. Kenny and Jordy’s parents weren’t “unkind,” at least they weren’t the sort of parents who beat you or locked you in the closet or forgot to feed you. But they were too wrapped up in their own lives to spare much attention for us. My parents would ask us questions and seemed to want to know the answers. And my step-dad had read most of the books we were obsessed with; he could talk about Frodo as easily as we could, and knew who Thomas Covenant was. My mom was great at giving out snacks and cooking meals and being fun and friendly. I’m not trying to be all glowy-eyed about my parents or anything. I’m just saying. And we’d go to Jordy’s house as well: that’s where we’d spend Friday nights and stay up late watching bad science fiction films on TBS, and as long as we weren’t too loud or silly Jordy’s parents would tolerate us.

But for a real sleepover--an all-night D&D event that could also include rude words, body noises, and behavior both loud and silly—it was always Kenny’s two story wood-sided house, partially because the dormer windows from his second floor bedroom allowed us access to the roof on summer nights, but mainly because his parents just didn’t care what we did as much as mine or Jordy’s did. Plus, Kenny’s house was closer to the woods, and there was always some fun to be had tearing up and down the scrubby dirt pathways between the trees.

Kenny’s father wasn’t there much, which meant that we were free to search his room for the Playboy magazines that were often stashed under his dresser. This was the most illicit thing I had ever done, looking at pictures of naked women in a magazine that would be returned before the owner missed it, and like everything it made me feel guilty. But I was probably going to feel guilty about something anyway, and I might as well get a look at some naked women for my trouble.

And the women weren’t all imaginary at Kenny’s house. His sister Courtney was in high school and also happened to be the neighborhood wet dream. Well, actually any girl in high school with long hair and visible tits was the neighborhood wet dream, but we got to see Courtney more often than the other girls in Riverwood. I had no sister, just a little brother who wasn’t old enough to do much more than interrupt TV shows or walk in on you in the bathroom. Jordy’s 10-year-old sister Becky was a pigtailed, freckled little terror who looked like Jordy, shrunken and in drag. She was no-one’s wet dream. Other girls were distant visions that none of us except Kenny could ever hope to speak to, but Courtney was a living breathing person who we could watch eat and move and sit in front of the TV. She even spoke to us, usually to tell us to get the hell out of the living room. She was pretty bitchy, but her body was poetry.

So I had high hopes for the weekend. On Friday morning I was putting my books in my locker before homeroom and Jordy came running up. He was out of breath and sort of spazzing, but that wasn’t unusual.

“Hey, Jordy. What’s up, man?” I kept digging for my social studies book. “you ready for this weekend? Brother Egbert is ready to kick some butt!” Brother Egbert was my twentieth level monk. He could levitate and do like a gazillion hit points damage in hand-to-hand. Jordy’s own character was a fighter named Franklin the Edgy. He was only eleventh level because he got hit by a time curse that wiped his abilities back three years. Jordy said that was unfair, but Kenny wouldn’t budge from it. Kenny’s always the Dungeon Master and he can be pretty hard and fast.

“I think I’ve got a better idea,”said Jordy. “Have you got Faerieswith you?” He peered into my locker.

“Yeah, it’s in there. I wasn’t planning on bringing it to Kenny’s, though. Why do you need it?”

“I’ve got a great plan for tonight.”

“What is it?”

“It’s a surprise. Just bring Faeries, okay? I’m so excited!” And then he did this weird little thing he always did—it’s like he’d bend his knees, shiver all over, and then straighten back up. In my head I call it “bivering,”but I never said this to Jordy. He was just too fragile.

Right at that moment Tiffany Harner and Karen Almers walked by. Tiffany made a snorty sort of giggle sound. She said, “God, what a spaz!” Karen laughed really loud and they both disappeared into Mrs. Shiels’ room.

“Jesus, Jordy,” I said. He looked after the girls.

“What?”

“Tiffany Harner, that’s what.” He still looked like he didn’t know what I was talking about, so I just said,“Come on, we’re gonna be late.”

I’d been in love with Tiffany Harner since fifth grade. She lived two streets over from me, about midway between my house and Kenny’s. She was blonde and taller than us and had a nose that looked like it was sculpted by Michelangelo or somebody. Kenny said that her tits weren’t big enough, and I always got mad because it felt like a betrayal to even listen to anybody talk about her like that. Plus, I thought she had really nice tits. Jeremy McMann said he looked in her window one night and saw her getting out of the shower. I didn’t believe him; he was always saying things like that. But I thought about it a lot. Sometimes I rode my bike around between her house and Kenny’s, hoping she would come out in the yard. I was scared one day she might come out in the yard.

One time in sixth grade Jordy told Tiffany that I thought she had a fine body. The next day Tiffany was right behind me in the lunch line and she leaned over to me and said, in a real low voice, “I hate you, Michael Oakley.” I acted like I hadn’t heard her. She hadn’t talked to me since. Jordy said he’d been trying to help.

In Social Studies we were learning about South Carolina history. Tom Cardinal sat at the back and threw spitballs at me and Jordy. It was really cliché, like something you’d see on TV. Tom was a big dumb kid, but in the seventh grade dumb doesn’t matter if you’re big, just like smart doesn’t matter if you’re fat, like me, or scrawny, like Jordy. Tom called us “Fatso” and “Flatso.” Trying to listen to Mrs. Shiels talk about General Francis Marion while spitballs are making a small, steady splat against the back of your neck is difficult at first, but even that early in the year it had just become part of class. We never said anything because we knew Tom would beat the shit out of us if we did.

Except that Friday Jordy did something completely amazing. About midway through class, he put down his pencil and turned around to look directly at Tom. Then he said, really loudly, “Why don’t you swallow those spitballs, you monkey-faced freak?”

I’ll admit that my first thought was that I was going to get beaten up just for sitting next to Jordy. But then I saw the look of pure gobsmacked disbelief on Tom’s face, and I knew it would be worth getting beaten up. I know it was a really lame insult. I mean, there were so many better things he could have said. I know because I used to lay in bed at night and think up really great and horrible things to say to Tom Cardinal. “Monkey-faced freak” was pretty good, but “swallow those spitballs” lacked all poetry. So the insult itself wasn’t so amazing. But the fact that Jordy had said it at all, that anyone would insult Tom Cardinal to his face, was supreme. And Tom was as shocked as the rest of us. He didn’t throw any more spitballs during that class.

After class, Tom waited for us by my locker. A crowd of kids stood in a rough semi-circle around us, so they all heard what he said. Tiffany Harner was in the circle, and I don’t know who else. Tom pushed Jordy up against the lockers. It looked like a grizzly bear holding a weasel. He said, “You’re fucking dead, Flatso!”There was a gasp from the onlookers.

And then, as if the day wasn’t already surreal enough, Jordy said, “If you think you’re big enough, then meet me in the woods behind Kenny’s house tonight at midnight.”

Tom relaxed his grip on Jordy’s shoulders. “What’re you talking about?”

“I’m talking about tonight,” said Jordy, “unless you’re scared.”

Tom got real close to Jordy’s face and said, “There’s nothing about you that could ever scare me, you pimply little dickwad. If you want to die at midnight, then you’ll die at midnight.”

See, that’s good dialogue, right there. That beats “swallow those spitballs” to pieces. Tom was dumb as a stump, but he could sure turn a phrase when he was promising violence.

The little crowd broke up before it drew attention from any teachers, and I was left staring at Jordy. “What did you do that for?” I said.

“It’s part of what I’ve got planned for tonight,” he said.

“What, getting the crap beaten out of you? And me, too, probably?”

“Just wait,”Jordy said, “it’s gonna be great.” And then he bivered again.

I opened my locker and saw Tiffany Harner watching us from her own locker, seven or eight down on the other side of the hall. Her eyes were really blue. She saw me see her and turned away, pretending to look for a book or something. I wondered if maybe Jordy was on to something. Were we suddenly cooler because we were going to die?

I spent forty-five seconds or so imagining Jordy getting killed by Tom Cardinal and Tiffany Harner comforting me at the funeral. She was wearing a black dress that ended mid-way down her thighs, and I knew she regretted how she had treated us all those years. Now that she had realized the extent of our bravery and sacrifice, she would make it up to me. She smelled like lavender, and her waist was soft under my arm. I closed the locker and went to lunch.

Kenny was waiting at our lunch table. Kenny had a couple notches on me and Jordy when it came to coolness. He was neither fat like me nor skinny like Jordy. His blonde hair was never combed but always looked right. His skin tanned easily. Kenny knew more than we did about life in general, and he used all the words we were afraid to. He had HBO, and had seen many rated R movies, the goriest scenes of which he recounted to Jordy and me with dramatic flourishes worthy of Gielgud or Olivier. It was sort of amazing that he wanted to hang out with us. He was interested in all the things we were—things which were definitely not cool, like hobbits and elves and alien monsters with ray guns. But even given all that, Kenny was cool, because some kids just are and that’s the way it is. He had supposedly even kissed a girl, but I had never had the guts to ask about that and could only rely on Jordy’s wide-eyed report.

“Jordy, what’s going on? Everybody’s saying you jumped on Tom Cardinal in the hall and bloodied his nose, and that he said he was going to break into your house and murder you.”

Jordy told Kenny what had actually happened. “But it’s no big deal,” he said, “I’ve got the best plan ever.”

“What is it?”Kenny asked. I looked at Jordy expectantly.

“You’ll see tonight,” Jordy said. He was really digging being mysterious. You could tell. “It’s gone on long enough. We’ll stop it all tonight.”

“Bullshit,”said Kenny, “what have you got planned?” It’s not like Kenny was in charge or anything, but we pretty much did what he said. “Tell me, Jordy.”

“Nope. Not ‘til tonight. It’s really awesome.” Kenny and I looked at each other. I swear sometimes it felt like we were Jordy’s parents or something. But Jordy wouldn’t say anything else about it, and seemed genuinely unconcerned about spending the weekend in the hospital. We talked about the D&D game and ate our hamburger-ish lunch.

* * *

The downstairs den at Kenny’s house always smelled like farts and Fritos, a fact which I attributed to the dog. Kenny’s dog was called Johnson. He was a sad animal who usually had something wrong with his ears. We never ceased being disgusted at the growths and funks that sprouted on Johnson’s ears. He also had the largest testicles I have ever seen on a dog. They swung and bounced as he walked and when he sat down they squashed together in a way that made us wince. Kenny called him “Old Iron Balls.”

But Old Iron Balls wasn’t around tonight—he was upstairs in Kenny’s parents room, sleeping. Conditions were perfect: Kenny’s mom had a bunch of sodas and chips and mini-Butterfingers and lemonade. We spread out across the floor of Kenny’s farty den, a cascade of food and paper and lead figurines and twenty-sided dice.

The campaign was awesome that night. Jordy had tremendous luck in the Chamber of Fungus, killing seven big orcs and gaining lots of experience points. It looked like Franklin the Edgy was on his way to regaining the levels he had lost last time we played. Kenny had some really surprising stuff waiting for us—he was really good at thinking up new situations and combinations of monsters. Brother Egbert did indeed kick butt, and by the time we took a break around ten o’clock I had two non-player characters serving as vassals on the expedition I was mounting to rescue the son of the High Rajah of Quelz.

When we stopped to eat, Jordy asked if I had brought Faeries. I pulled the book out and handed it to him.

“Okay, Jordy,”I said, “what’s up? Please tell us what’s going on.” Even though we’d been having fun, Kenny and I had both been painfully aware that the showdown with Tom was approaching. Personally I was hoping Jordy was going to pull a no-show and that Tom would be content to just humiliate us at school on Monday for being chicken.

“Here it is,”said Jordy, and pointed to a page in the book.

We were all enthralled by Brian Froud and Alan Lee’s Faeries. I had at first thought it was a cheap rip-off of Gnomes, which was my favorite book two years before. I had bought it anyway, and had realized how wrong I was. Jordy was fascinated by the pictures of naked faeries in the book, which were numerous. To be honest I liked a few of these as well, but it seemed to cheapen the whole thing to reduce it to sex. The pictures, the stories, and the handwritten text were magic in themselves, but more importantly they pointed the way to a reality that lay just beneath the surface of the everyday. It was a sort of talisman representing everything we were about.

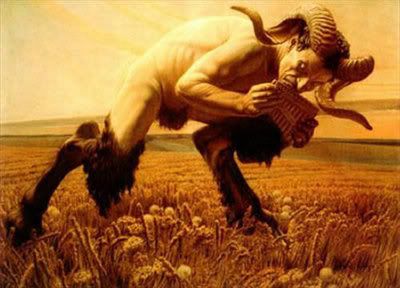

The drawing Jordy pointed at was spooky and realistic—a thin man covered in scraggly black hairs and topped with the head of a truly demonic goat. We all knew the Phooka (pronounced “Pooka,” the book helpfully pointed out). It was an Irish faerie that took the form of a black pony or goat and took unwary travelers for wild rides through the underbrush before dumping them in a ditch. All the travelers in Froud and Lee’s folktales were unwary. The Phooka frankly scared the shit out of me, but of course I never said that to Kenny and Jordy. Right then I just wondered why Jordy was pointing to the thing and looking at me and Kenny as if he’d explained something.

“It’s the Phooka,” said Kenny. “So what?”

“Damn right it’s the Phooka,” said Jordy, “and there’s one living in the woods behind your house.”

Kenny had this way of saying “What?” that was sort of drawn out and high-pitched and made you feel like you’d just said the stupidest thing anybody had ever said in the history of talking. He did it then, and I have to admit Jordy had earned it.

“That’s crazy, Jordy,” I said, “Phookas are from Ireland.”

Kenny gave me the same Look he had given Jordy. “Plus they don’t exist, you dildoes.”

Jordy chose to answer me. “I know they’re from Ireland originally, but there’s one here. I’ve seen it. Walking in the woods at night.”

“You’ve seen a Phooka walking in the woods behind Kenny’s house?”

“No, I’ve seen a Phooka when I was walking in the woods at night.”

“What was it doing?”

“Just sitting in the bushes next to the creek, staring at me.”

“Jesus, Jordy, that’s creepy as hell!”

“It’s not creepy,” said Kenny, “it’s bullshit. What were you doing walking in the woods behind my house?”

“Just walking. Looking around.”

“How can you look around in the middle of the night?” Kenny wanted to know. It was a good question. Even more shocking than the fact that Jordy thought the woods had a Phooka was the fact that timid little Jordy would walk in the woods by himself after dark. I sure wouldn’t have.

“Alright,”said Jordy, with the air of someone who’s come to a decision, “I was looking for faeries. I wanted to find faeries like the ones Brian Froud and Alan Lee found.”

Kenny started laughing. It was small giggles at first, but it quickly became obvious that Jordy was getting pissed off and that sent Kenny into full-on belly laughs. Guffaws even. I mean seriously, I thought we’d have to get him oxygen. Eventually Jordy shouted “What’s so funny?” and then I started laughing.

Kenny sobered up first. Jordy was angry, but not the sort of red-faced, close-to-crying angry that he did two or three times a day. His voice was very quiet and controlled. He said, “If you two retards are done making fun of me, I’ll tell you my plan.”

I said I was sorry. Kenny didn’t. Jordy looked down at the book. Rick Springfield was singing “Jesse’s Girl” on Kenny’s boombox. “Lately something’s changed,”sang Rick, “it ain’t hard to define.” Jordy looked up.

“Ihave seen a Phooka,” said Jordy.“I’ve seen it three times, and I know where it is. It’s always near the same bend in the path. I’ve seen other things out there too, but the Phooka’s the one. I’m gonna lure Tom Cardinal out to the bend in the path and I’m gonna let the Phooka get him.”

This time we didn’t laugh. Kenny didn’t even give him the Look. Instead Kenny said, really reasonably, “But that’s crazy, Jordy.”

“Why? Forget about you not thinking it’s real. I know it’s there. So why is it crazy?’

Kenny thought. “Well,” he said, “how can you be sure the Phooka will want anything to do with Tom Cardinal? And if it did, wouldn’t that be like murder or something? Tom’s a dick, but you can’t go around getting people killed because of that. Half the school’d be dead.”

“The Phooka doesn’t kill people. It plays tricks on them. It scares the bejeezus out of them.” We all looked at the picture of the Phooka. It was dead scary. “And Tom’s more than just a dick. He’s a horrible person. He’s bad. He deserves anything we can do to him.”

It was getting maximum weird now. The faerie thing was out there, but Jordy’s talking about Tom Cardinal was worse. It was too serious or something. It was adult.

Kenny said,“Why would it do anything to Tom at all? Why hasn’t it done anything to you while you’re mounting these expeditions all over the woods in the middle of the night?”

“I think it’s waiting,” said Jordy. “I think it will get Tom because he deserves to get got, and the Phooka will know that.”

“Okay,” said Kenny. “Maybe you’re right.” I looked at Kenny. Were we all losing it?

“I know I’m right,” said Jordy, his voice finally quavering just like old times, “I just need to know if you guys are coming with me.”

During the pause after Jordy spoke, I looked out the window at the darkness. On the radio, Phil Collins could feel it coming in the air tonight. I tried to see Tiffany Harner’s house, but it was too dark and the angle was wrong. Then, as I watched the window, I saw something move. It was really hard to tell what was what, looking out into the darkness from a brightly lit room, but I swear I saw a wrinkled face under a wide-brimmed hat looking in the window. I sat very still. When I tried to make the face out it wasn’t there any more. Jordy’s craziness was getting to me. I didn’t say anything to Kenny or Jordy, since I probably imagined it and I didn’t want to look like a scaredy-cat. Then Kenny surprised me again by saying, “Yeah, Jordy. Sure we’ll come with you.”

Jordy had a lot of equipment in his backpack. “It’s gonna be a real faerie hunt,” he said, pulling out flashlights and bottled water. “I mean, we’re going to really give it to Tom Cardinal good, but we’re also gonna see some really amazing stuff. I’ve already seen the Phooka, and what I think was a Fir Darrig, and I think there’s things living in the creek. Goblins, maybe. With all three of us looking, there’s no telling what we’ll find!”

Referring to the two-page spread that details how to protect yourself from faeries, Jordy had chosen the most convenient and easy to use items. He had a zip-loc bag full of salt for each of us, and some sprigs of a plant he assured us was St. John’s Wort. He also had us turn our shirts inside out. The most impressive thing he had was his father’s hunting knife, a big, wicked-looking thing with a long leather-sheathed blade and a bone handle.

“What’s that for, Jordy?” I asked.

“It’s got iron in it,” he said. “they hate iron. You know that. Plus it might come in handy if we get in a tight place.”

After we’d redressed and Jordy had packed our protection kits, he went to the bathroom. I turned to Kenny. “What are you doing?”

Kenny looked in the direction Jordy had gone. “We’ve gotta look out for him, Mike. He’s really gone off the deep end.”

“So you agree this is crazy?”

“Oh, it’s bugshit crazy. But Tom Cardinal’s real, and he’s gonna beat Jordy ‘til we can’t recognize him. It’d be better if there were three of us there, and if we could keep Jordy from threatening Tom with faeries. We’d never hear the end of it.”

“I’m just.” There was nothing outside the window now but darkness. I swallowed and took the plunge. “I’m a little scared, is all.”

“Shit, yeah,”said Kenny. “Tom Cardinal’s gonna have us for breakfast.”

* * *

It was 11:25 when we left the house. We each had a flashlight, a bag of salt, a sprig of St. John’s Wort, a green pocket-sized New Testament, and an inside-out shirt. Jordy had a camera and the big hunting knife stuck in his belt. He had made three long daisy chains, one for each of us, but Kenny had put his foot down at that.“If Tom Cardinal’s going to beat the crap out of me,” he said, “he’s not doing it while I’m wearing a bunch of frickin’ flowers.”

At the edge of the woods we stopped and looked around, like we were in some spy movie or something. The houses of Riverwood were laid out in neat rows, lining streets that intersected each other at regular right angles. The light from TVs spilled out onto the close-cut lawns, under the pair of pine trees that grew in each yard. The scene was comforting; our whole world was in these streets, except for the school a mile and a half away. From here I could see Tiffany Harner’s house. There was a light on in the upstairs window that I thought was hers. I wondered what she was doing up at 11:30, what she was thinking about.

Turning our back on Riverwood, we entered the woods. I guess the woods behind Kenny’s house weren’t really all that big or deep. They were maybe three hundred square yards, but they were thick, filled with underbrush and sticker-bushes. I had to do this stupid leaf project in the sixth grade where we collected leaves from twenty different kinds of trees and put them in this leaf journal. I know there were at least sixteen different kinds of trees in the woods, because I had to get the other four from my Grandma’s house, but they were mostly pine, like all woods in South Carolina. There were three or four paths wandering among the trees, dusty and twisted, and a small creek that flowed through the middle. The woods sloped down towards the creek and then back up again on the other side. The creek flowed in places and in others just sort of stood there. The best path ran right alongside the creek, down at the bottom of the woods. At 11:30, it was stupid dark.

We took the main path, sloping down and to the right. Jordy wouldn’t let us use the flashlights, because it would scare away the faeries. I asked Jordy where he was supposed to have his showdown with Tom Cardinal, and he said that the woods weren’t that big, and they’d find each other eventually.

In the dark, I started seeing things. The path was dusty pale in front of me, and I could just make out shapes at its edges. I thought I saw all sorts of things before we were fifty feet in—goblins and leprechauns and taller, more sinister things. They didn’t move, and I knew they were just shadows and trees and the after-effects of Jordy’s crazy talk and the pictures in Froud and Lee. They scared me shitless just the same. I clutched my bag of salt and said the Lord’s Prayer as well as I could remember it.

We reached the big junction where three paths came together. Behind us was Kenny’s house and Riverwood, to our left was the path by the creek, and ahead and slightly to the right was a smaller trail that would eventually come out in the ditch next to the Pamplico highway. Jordy stopped and took out his bag of salt.

“Okay,” he said, “I’m going to make a safe circle here.”

“What does that mean?” I asked. “Safe from what?”

“From anything that we find or rile up that doesn’t want us out here.” He popped the zip-loc and started pouring the salt out around himself in a wide circle. Then he crushed his St. John’s Wort and sprinkled it over the ground inside the circle. I had just read Dracula, and Jordy seemed all Van Helsing-like while he did this; very matter-of-fact. “Now, if we get into trouble, we just have to get back here, in the middle of this crossroads, and jump into the circle.”

“That salt ain’t gonna keep Tom Cardinal off of you,” said Kenny.

“The Phooka will take care of Tom,” said Jordy.

“Oh, that’s right,” said Kenny, “I forgot.” He didn’t seem scared at all. It was hard to see his face in the darkness, but I could feel the sarcasm coming off him. He was worried about Tom Cardinal, but he wasn’t scared of anything living in the woods. Why was I? I wouldn’t have said I believed the stuff in the Faeries book, but out in the woods in the dark all bets were off. I wanted to go home. I was careful not to say this. I wished I could be as cool as Kenny.

“But now you don’t have any salt or St. John’s Wort,” I said, earning a Look from Kenny.

“I’ve got the knife and the Bible,” said Jordy. He was also unperturbed. I wondered whether I was just the biggest wuss of the three of us.

Jordy pointed down the path by the creek. “That’s where the Phooka is,” he said, “about halfway down at the big bend in the path. It’s always sitting in the bushes across the path from the creek.”

“So, what do we do?” I asked.

“First we hunt,” he said, “and see what we can find. Then, at midnight, I’ll come back here to the salt circle. You and Kenny go down the path to the where the big willow hangs over the creek. Tom’ll have to come here, if he comes in from Riverwood, and when he sees me I’ll start running. I’ll lead him down to the Phooka. When we pass you guys, you come out on the path and block it so he can’t run back.” He turned on his flashlight and looked at his watch. “It’s twenty minutes to twelve. Let’s go.” It was so bizarre to have Jordy in control like that. We just went and did what he said.

I didn’t find any faeries during our twenty-minute “hunt.” My eyes had finally adjusted to the dark more or less, and I could see trees and shrubs by the path for what they were. I heard lots of rustling and stuff that I really didn’t like, but I knew it wasn’t goblins or redcaps. It was most likely squirrels or raccoons. I could hear bigger noises from a couple of different directions, like somebody walking in the underbrush, but I knew that was Jordy and Kenny in other parts of the woods. I was still scared but liked this better; it was creepy being alone, but it was a different kind of creepy than what Jordy was putting out tonight. I didn’t go near the bend in the path where he had seen the Phooka.

At three minutes to midnight, I was on the path by the big weeping willow. Kenny was already there. I asked him if he’d seen any faeries and he hit me in the arm.

Kenny looked over his shoulder to see if Jordy was anywhere around. There was no sign, he must have already been back at the salt circle. “Listen, Mike,” he said,“there’s no Phookas out here.”

“I know that,”I said. I glanced down the path toward the bend.

“But there is gonna be a huge red-headed monster. Tom is gonna be real, and we need to be ready. Here.” He tossed me one end of a rope he pulled out of his backpack. It was a yellow nylon thing like you buy at a camping store.

“What’s this for?”

“Take one end of it and go into the bushes over there, just like Jordy said. I’ll take my end into the bushes on the other side of the path. In a few minutes Jordy’s gonna come running through here with Tom Cardinal hot on his heels. As soon as Jordy passes us, pull the rope as hard as you can.”

“We’re gonna trip him?”

“We’re gonna knock him flat on his face. He won’t know what hit him, and then we’ll haul butt out of here.”

“Which way?”

“What?”

“Which way do we haul it out?”

“Oh. Good point. We’ll run that way.” He pointed further down the path. “So we can grab Jordy and haul him out with us.”

“Okay. Cool.” It was a good plan. Solid, with a pretty good chance of success. It didn’t rely on imaginary goat-men, and the odds were in favor of us not getting beaten to death until Monday. I liked it. I took my place in the bushes under the hanging branches of the willow, next to the creek. I couldn’t see Kenny across the path in the darkness, but I could feel the rope tighten in my hands as he took his place and pulled up the slack.

The time drug, laying there in the pitch black. Jordy didn’t come, and I didn’t hear anything from that end of the path. It was around two hundred yards from the salt circle crossroads to the bend where Jordy said the Phooka was. We were roughly halfway between the two. The woods were much quieter around me than they had been during my hunt—probably because the three of us weren’t tromping through the bushes like Paul Bunyan. I lay there and waited.

It seemed like much more than three or four minutes had passed. I couldn’t turn on the flashlight to look at my watch because Jordy and Tom could come at any moment. But I could have sworn they should already have been there. I wondered if something had gone wrong. Had Tom caught Jordy by surprise? Was he pounding him into a pulp right now? I still couldn’t hear anything. I lifted my head and looked back up the path.

And I saw Tiffany Harner. Like me, she was in the bushes on the creek side of the path, but she was standing up and facing the water. It looked like she was walking down the bank towards the creek. She was turned three-quarters away from me, and it was dark, but I could tell Tiffany from a mile away. Her blonde hair hung down to the small of her back and shone like a beacon in the gloom. She was wearing a long, light colored dress that I had never seen before. It might have been green. At first I had no idea what Tiffany Harner would be doing in the woods in the middle of the night, then I remembered her watching me and Jordy after Tom had threatened Jordy in the hall. She must have come to see what happened. I didn’t know whether she’d be cheering for us or Tom Cardinal, but there she was. She hadn’t seen me.

I turned a little in the dirt to see her better. She walked down until her legs were calf-deep in the water. What was she doing? The bottom of her dress floated around her legs. I half-crouched and moved closer to her. I stopped a few yards away, afraid she’d hear me. Her back was to me now. The dress clung to her like nothing I’d ever seen her wear. She was looking down into the water.

Then she did something that was straight out of my dream world. Tiffany Harner lifted her hands to the top of her dress and pulled the shoulders down. The dress slid off her in one smooth, even movement. She was naked underneath. I could see her entire back, head to calf, and the side of her right breast.

I didn’t know what to do. I’d spent years imagining Tiffany Harner naked, but these were weird circumstances. I felt like I should say something, let her know I was there. She clearly didn’t know I was anywhere nearby. But maybe I was already in trouble for seeing what I had seen. And when would I get a chance like this again?

She turned towards me, still looking down at the water. Facing me now, she was the most astonishing thing I had ever seen. Her hair hung down across her face and just grazed the tops of her breasts, the skin pale and almost translucent in the dim light. The dark tangle between her legs was suspended there ten feet from me above the water. In all my short life, I had never felt longing like I did right then, looking at the glory of Tiffany Harner’s body. The moment seemed to last a long time. Then she raised her head and looked at me.

It wasn’t Tiffany. I don’t know how I ever could have thought it was. Her hair, for one thing, was dark and much longer than Tiffany’s, curling and looping down her back and around her breasts and waist. Her face was achingly beautiful, but wilder than Tiffany’s, and older. Her body could still be that of a girl, but her eyes seemed very old—they were darker as well, not icy blue like Tiffany’s. She looked directly at me and smiled. It was a mocking and wicked smile, though not completely unkind. I felt ridiculously young and stupid. I was way out of my depth, and her smile told me that we both knew it.

The woman in the water took a step toward me, and as she did she seemed to grow larger somehow. Her arms stretched and rubbered out, her fingernails lengthened and curved, her face darkened and her eyebrows arched and bushed. Any longing I felt was gone. She raised her right arm and pointed a long, tapered finger at my chest, and then she melted. I mean that—she collapsed like a column of water into the creek, pushing a wave of warm, moist air against me that shook my clothes like a breeze.

Immediately I heard a yell from back towards the salt circle and then the sound of galloping hooves on the path. I turned around, completely disoriented. I stumbled back up the bank and emerged on the path. Something was coming up the path towards us, fast. I heard another yell, but I couldn’t tell what they were saying, or who it was yelling. I called out Kenny’s name.

Kenny came out onto the path. “What’s going on?” he said, and before I could not answer him, Tom Cardinal came running down the path. Tom’s face was white, and he looked more scared than me. He was really moving. Jordy was nowhere to be seen. I jumped back as he came up with me. I don’t think he even saw me. Kenny saw him coming, stuck out his foot, and tripped him.

Tom Cardinal hit the ground with his face hard enough that I felt it from five feet away. Kenny stepped back from him and watched. Tom got up real quick. His face was bleeding from two or three places and his nose didn’t sit right. He looked at me and Kenny like he didn’t know who we were. Then he looked back up the path where he’d come from, turned around, and ran as hard as he could go. He disappeared around the bend.

Kenny and I looked at each other. I started to say something, but right then we heard someone back up the path start laughing. At first I thought it was Jordy, but then it went on longer and it sounded like something else. It was high and hysterical and abolutely batshit. Nothing in that whole screwed up night had scared me like the sound of that laugher. It went on way too long, while Kenny and I just looked at each other.

After it died away, Kenny said, “Shit, Mike, what was that?”

“I don’t know,”I said.

“Let’s find Jordy and get out of here.”

It was really quiet as we walked back up the path. Kenny said, “Mike, I saw something, while we were waiting.”

I said, “Me, too.” The image of the woman in the water was burned in my brain. “What did you see?”

“I…” He frowned. “I don’t know. What about you?”

“I don’t know either.”

The ground was all torn up at the crossroads, maybe because of Tom Cardinal running around. The salt circle was still there, mostly, but one side had been smeared away in a muddle of footprints. Off to the side of the path we found Jordy’s knife. It had some blood on it, not much, but a little, smeared along the sharp edge of the blade. That freaked me out. The woods stretched out around us, silent and still. Jordy wasn’t there.

Kenny and I looked at each other across the salt circle. We were each thinking, maybe, about what we had seen in the trees before Tom came running down the path, things we’d never share with each other. We were scared, but only backhandedly. There was nothing left to be afraid of. We could see the lights of Riverwood through the trees. And Jordy was gone.

We looked for another hour or more. We walked down every path, calling Jordy’s name. We pushed through the brambles and sticker-bushes by the stream, and climbed up to the edge of the Pamplico highway and looked both ways along the verge. Jordy was not in the woods, or by the stream, or on the highway, or back in Riverwood. He was gone.

We ended up back at the crossroads. The knife was still where we had left it, laying in the dirt beside the smudged safe circle. The blood on its edge had dried to a rusty brown. I dropped to my knees by the salt circle and started to cry. It was a baby thing to do, but I couldn’t help it. Kenny watched me for a while, and then he helped me up.

The light was off in Tiffany Harner’s room as we stumbled back to Kenny’s house. We went inside and up the stairs, passing the den with its litter of food and paper. In Kenny’s room we lifted the sash and climbed out of the window. We sat on the roof of Kenny’s house and watched the sun rise. Tomorrow morning it would all begin—police and parents and tears and Tom Cardinal’s psychiatric treatment. But at dawn Riverwood looked exactly the same. Nothing had changed.

*

* *

What inspires you to write and keep writing?

Other writers. Like most authors, I am a voracious reader. Reading good writing inspires me and makes me want to try harder. I love beautiful prose, and the tension and release of a well-constructed narrative. A Peter Straub novel, a Kelly Link short story, an episode of Buffy, these are gaslights on my cobbled alleyway. And coffee. Coffee.

2 comments:

You know, middle school sucked quite a bit for me too, but faeries never killed any of my friends. Yet somehow, this scared the crap out of me. Nice work!

I'm glad you liked it! Middle school is a harrowing time. Glad you never lost any friends to the faeries.

Post a Comment